HAMILTON-- When French President François Hollande announced that French armed forces would provide support to the government of Mali, he was careful to add "[T]he operation will last as long as necessary.” The original request for military assistance came from exiled Malian President Amadou Toumani Touré, ousted in March 2012 by elements of the Malian military, in protest over Touré's handling of the Tuareg rebellion.

As of February 22, there were nearly 4500 French troops are on the ground, according to France's top soldier.

The French government has suggested this is a mission of liberation, to free Mali from the growing threat of Islamist militants. However, this narrative appears to echo the familiar ''war-on-terror" rhetoric that served to escalate the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Canadian government has supported this mission by providing a C-17 military transport plane, and setting out a vaguely defined role for the Joint Task Force, Canada's special forces.

Hollande stressed that “France is intervening to stop al-Qaeda-linked fighters in Mali who have been moving toward the capital, Bamako”. The mainsteam Canadian media has been quick to pounce on the by-now familiar al-Qaeda narrative. Yet this framing ignores the deeper ethno-political cleavages of the region.

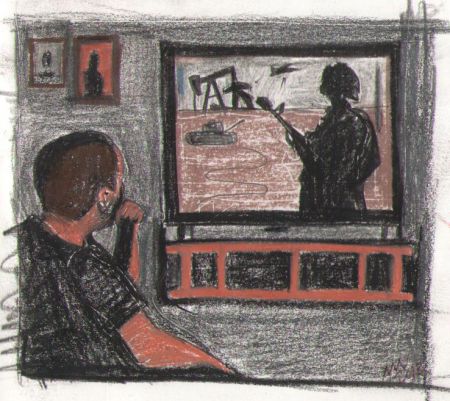

In the weeks since France launched its military intervention in Mali, major Western media outlets appear to be following a "war on terror" framing of the conflict, focusing most attention on the activities of "Islamist militants" in the region.

Thomas Woodley, President of Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East (CJPME), highlights that the media plays a role in perpetuating this problem. “[The] stories are too brief... they are often just soundbites” and major sources are “not asking the questions that need to be asked,” he said.

Western headlines have gone far to sensationalize the fear of Islam. CNN ran a story about a French family abducted by Islamist militants, while the CBC reported on three unmarried couples being publicly whipped by militants in Timbuktu. Other stories focus on "clashes with radicals" in "critical operations," Islamists extending their control southward, or celebrating the French capturing "the last remaining Islamist 'stronghold'". All major Western sources covered Hollande's photo-op visit to Timbuktu, hailing him as a 'saviour' to the people of Mali.

Although the spread of radical Islam across the country is indeed a major issue, a key problem in Mali (and surrounding regions) appears to be the mishandling of the Tuareg nationalist movement, an issue that has largely escaped mainstream media analysis.

“There is no coverage of the ethnic Tuareg,” explains Woodley. “Headlines focus on Islam, but Islam is not the issue in Mali... the country is predominately Muslim.”

Mali, Algeria, Libya, Niger, and Burkina Faso are all home to Tuareg minorities living on land with abundant reserves of oil, gas, uranium, and other valuable minerals. For decades before the January 2012 rebellion in Mali, Tuareg leaders maintained that their people were being marginalized and impoverished, and that mining projects have damaged pastoral areas important to Tuareg livelihoods, economic independence and culture.

An Oakland Institute report on cases of large-scale land investment in Mali concludes that several major problems characterize the recent foreign investment trend. The report highlights a lack of legal obligation in contracts to conduct environmental or social impact assessments, and an ignorance of local communities' land rights, often leading to violations of basic human rights of the people affected.

The Tuareg rebellion that ousted the Mali government stemmed from these ongoing tensions, as well as the aftermath of the Libyan civil war. Thousands of Tuareg rebels fought on both sides of the conflict in Libya, and many returned well-armed to Mali following the defeat of Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi. From January to April 2012, these rebels waged war against the Malian government for the goal of Azawad (northern region) independence.

Khaoula Bengezi, a recent MA graduate from McMaster University, was on the ground in Libya during the civil war. She explained in an interview with The Dominion that the Tuareg minorities in Libya were often treated with “prejudice and suspicion”, given their strong support for Gaddafi.

The Islamist groups who have so far attracted the majority of media attention began fighting for the rebellion, but following the government coup they seized control of much of the northern region of the country. Some commentators describe the actions of radical groups as an "opportunistic takeover of the rebellion."

Terrorism is a problem in Mali, however it cannot be approached without contemplating other grievances in the region. Intervention by Western powers against militants ignores the Tuareg's situation, which critics worry will only re-emerge if left unaddressed. Yet the media, in following the French strategy of singularly addressing Islamic terrorism in Mali, has adopted this narrow framing of the conflict.

Woodley highlights that there is little mainstream discussion of "what's next" for Mali, noting “conflicts don't flare up then disappear.” Woodley likened Mali to Afghanistan during the Soviet War. “[A]fter the Soviets withdrew, a power vacuum was created which allowed mujahideen groups to seize the region ... the people of Mali need stable institutions, structures, and processes,” he sadi. Citing journalist Robert Fisk, who recently gave a talk in Hamilton, Woodley reiterates a different approach to the conflict: “[D]on't send military intervention, send bridge builders, send agronomists, and send people who can help build their infrastructure."

Canada has committed $13 million in emergency aid to Mali, in addition to about $70 million in ongoing, long-term aid to help train armed forces in neighbouring Niger.

The Canadian government asserts that this strategy contributes to the campaign against Islamist militants without a direct military intervention. However, Canadian interest in Mali does not appear entirely altruistic. Canadian aid to Mali is largely tied to products and services procured in Canada.

Canadian companies are also among the biggest investors in Mali. As of 2010, at least 15 Canadian mining and exploration firms were operating in Mali, with estimated assets of $230 million.

Considering the depth and scope of problems in Mali and West Africa, a different lens - one that looks beyond colonially imposed boundaries - is necessary.

“The best approach is to look at West Africa as a region, not country by country,” said Frederic Mousseau, Policy Director at the Oakland Institute in an interview with The Dominion. “Borders were drawn with a ruler by colonial powers. Many conflicts are related to these borders that don't make sense ethnically or economically... a regional lens could solve many problems we face today, whether they are economic or political.

“Look at the example of Europe... economic integration also brings peace ... a stronger West Africa will allow the region to better deal with internal matters, but also vis-a-vis the outside world.”

One hope for regional integration is the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

Formed in 1975, ECOWAS represents 15 member states whose mandate is to promote collective self-sufficiency for its members by creating a large trading bloc and coordinate a regional agricultural program (ECOWAP) to address food security.

Peace and stability in Mali and West Africa may be achieved through stronger regional integration, but barriers - many of them exterior to the region - remain. “Many don't want a strong West Africa," notes Mousseau. "They would rather deal (economically and politically) country-by-country."

Clearly there is more to the story in Mali and West Africa than security and terrorism.

Yet, as of February 14, 2013, Canada has extended its C-17 mission for an additional 30 days. NDP foreign affairs critic Paul Dewar said the extension was a "surprise" and made without consultation with the Opposition. Canada's one-week C-17 mission has already been extended twice, raising concerns of '"mission creep", suggesting that Canada's role in Mali will be deeper and longer-lasting.

Woodley points out an important caveat in the coverage of Mali: “Short articles can't possibly cover the issues (in Mali), but short articles are what people want to read... the onus is on the public to demand better coverage of the issues”.

Sean Pittman is an MA graduate from the Institute on Globalization and the Human Condition at McMaster University and currently resides in Hamilton, Ontario.