Can you start off by telling us who you are, where you come from, and why you are a land defender?

I’m Freda Huson, spokesperson for the Unist’ot’en. In my home community, we were taught to respect and take care of the land from a young age. Ever since we were young, we were taken onto the land and were taught to take only what we need so we don’t overexploit our resources. Right now, industry overexploits all the resources. All the industries that have come and gone – like the fisheries and logging – have completely depleted the resources. They’ve continually shown that they can’t manage resources. We’ve been forced to come back to the land to ensure that they’re not going to destroy it as they have done to other areas.

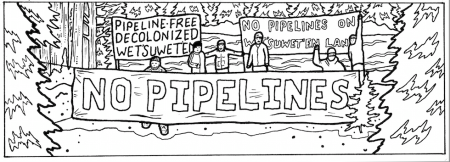

Do you want to tell us about the pipelines your people are resisting?

The first one was Enbridge’s Northern Gateway Project. Pretty much everyone across BC was opposed to it because it was proposed to carry diluted bitumen. Right now we’re battling what’s being called liquefied natural gas (LNG). But it’s not natural gas – it’s fracked gas. The way they process it and get it out of the ground is toxic. They’re proposing to come through the remaining 10% of my people’s territory: Unist’ot’en.

Companies are ignoring our governance structure, the hereditary system, and are trying to strike deals with band councils. Band councils don’t have any jurisdiction off the reserves. They were created by the federal government to run the reserves which were created to keep us off our lands. All they do is implement the policies of the Indian Act. Our system does not operate according to the Indian Act. We do everything in our feast hall and decisions regarding our land are decided within the clan. We can’t make decisions about other clans’ territories: that’s their responsibility. We’re conscious of our neighbours and we ensure that our decisions are not going to impact them adversely.

What threats to your lands do these pipelines pose?

Our salmon is at stake. The salmon spawn here and go into the Morice, Bulkley, and Skeena Rivers before they head to the coast. The Morice is the one of the only rivers we can still drink from directly. The grizzlies depend on the salmon for their food source. There’s also a lot of medicines and berry patches that the pipeline route would wipe out.

Just this past summer they were doing some prep work and they blocked people off the territory. If they put permanent structures in here, we’ll be blocked off from the vast majority of our territory. Like I said earlier, we only have 10% of usable land left because a lot of Wet’suwet’en has been taken over by agriculture and municipalities. They want to put pipelines through what little we have left. This would severely restrict what we could do on our lands because, guaranteed, they’re going to have gates and fences up if they put these projects through. Furthermore, they can’t say that the gas is just going to dissipate into the air if there’s a leak. It could cause an explosion and/or wildfire that would destroy massive tracts of land. They’re not telling people the full truth.

Although our struggles are being portrayed as separate, Lelu Island’s Flora Bank is a nursery for our salmon until they mature and travel up to Alaska. After two to four years, they come back here. So an LNG plant on Lelu Island still impacts us people upstream. In our culture, we ensure that whatever we’re doing on our lands is not going to adversely impact those downstream. Our salmon are the most important thing we would lose; in Russia, we know that the salmon disappeared ten years after the LNG plants opened. All of these projects are connected and are going to impact us.

The Unist’ot’en are part of the Wet’suwet’en territory and your land remains unceded. What does this mean?

We have never given up our lands whether it be through war or treaty. We’ve never given it up to the province or the federal government. Unceded means it’s still managed by my people. Our hereditary system is still intact and we proved that with the Delgamuukw v. BC court case. We were always on our lands and we’ve never signed any treaties. We have given up neither the rights to our land nor the rights to make decisions for ourselves.

When did the Unist’ot’en camp begin and how did it all start?

We started having the action camp in 2009. For two years, we would just come out, set up, and return to my home community. After the second year of doing this, industry tried to come in here even though we had responded to their letters saying that we didn’t approve of their project. They flew in drilling equipment and tried to drill the night of my brother’s wake. We received notice that the drilling company was planning to go in at 5 AM so my partner Toghestiy said he could come up here instead of going to tomorrow’s funeral. He came here with my uncle and my cousin around 2 AM. At 5 AM the drillers showed up. Toghestiy told them that they couldn’t come in and had until Friday to get their equipment out of here. They left and only came back for their equipment.

From that point on, we decided we had to live here because we couldn’t monitor it from two hours away. We knew they were relentless, and wouldn’t stop what they were trying to do unless we actually occupied the land. My dad always told me, “The only way you’re going to protect your land is if you occupy it.”

Our goal is to be a model so people can see we’re doing this successfully and that they too can move back to the land. That’s the ultimate goal: we’re hoping to get our Wet’suwet’en people living back out on the land. It’s our right to be out here and the reservations are like little prisons with small tracks of land and overcrowded housing. The Indian Act system is set up to oppress the people. It’s designed to keep people on the reserve so that they can keep us off our lands.

The Unist’ot’en camp has been described as a reclamation of traditional territory. Can you explain what the significance of living on the land again has meant for your people?

We’ve reoccupied our land to try and revitalize it. A lot of it has been destroyed by clear-cut logging. We took a quarter of a cut block and developed a permaculture garden there so we could grow our own food and save some of our medicines and berries. We just have to take care of it for the first few years and after a while it will take care of itself. We’ve been living off the land and monitoring how much wildlife is starting to come back. We’re trying to manage our resources so they’ll be there for the next generation. The only way we can do that is by monitoring who comes in and what they’re doing.

We practice free, prior, and informed consent. We ask a series of questions to people before we let them in: “Who are you? Where are you from? How long do you plan to stay here? Do you work for industry or government that’s destroying the land? What kinds of skills do you bring? How will your visit benefit Unist’ot’en?”

You’ve had to deal with a number of threats, not only from industry and the police, but also from settlers. What are some of the issues you had to face, and in particular, would you be able to speak to the pipe bomb incident?

I think that was about 3 years ago. We were all inside watching a movie in the cabin and then, all of a sudden, we heard a loud explosion. When everyone got to the bridge, we saw that someone had tried to blow up one of our signs that was blocking the road. When we called the police about it, they did a cursory investigation and left. We never heard anything more about it. A week prior to that, a hunter came to warn us. He said a young group of men were saying that they were pissed off that they couldn’t come up here and that they were going to deal with us. I shared that information with the police and again, they didn’t do anything about it. More and more, we’re realizing that the police are actually working with the companies.

More recently, a white pickup with a big bright light came to our bridge, revved its engine, and spun a circle before it left. Then, about two weeks ago, two supporters went into Houston and on their way back at the seven km mark, the same white vehicle and another pickup zoomed passed them and boxed them in. The two vehicles were parked facing our supporter’s vehicle, shining their lights on them, and another pulled in behind them. One of our supporters got out and shouted, “What the heck?” When the guys in the trucks saw they weren’t Indigenous, that they were just settler supporters, they let them go.

Since your camp was first established, you’ve hosted annual action camps and have been open to volunteers. What happens at these camps and how can people get involved in helping out?

We’ve had six annual action camps and each year there are different presenters. The majority of the camp is about decolonization, how to speak to the media, and how to keep yourself safe. Those who come learn a lot about our culture, how we do things, and why we do things the way we do. We’re sharing our knowledge on how to protect the environment and minimize our impact on the planet; if we don’t start minimizing, the little that we’re doing here is not going to make an impact at all. We need to stop thinking that we need stuff stuff stuff; because this stuff stuff stuff is filling up our landfills and requires oil and gas to produce. Take care of your things and make them last.

What are other ways people can support you?

Educate yourself on fracking: what it does to the planet, and how it’s going to impact you regardless of where you live. Only 2% of water on the planet is freshwater. If we use it all up we’re going to kill ourselves off as a human race. It doesn’t matter where the fracking is happening. All water is connected regardless of where you are. People should educate themselves and others because the mainstream media doesn’t properly inform the public about the destruction industry causes. They’re not going to report against the people that fund them. We must shatter the illusion that fracking will not have adverse consequences for our children and grandchildren.

Have you noticed a difference in strategy from the representatives of industry?

Divide and conquer has been the strategy of choice for the past hundred years. They hire people from our families and communities to sow division. We’ve got to be smarter so that we are fighting industry instead of fighting ourselves. Our people will always live here whether they take industry jobs or not, and they will have to live with the consequences of their choices. Meanwhile, industry reps can go back to their cozy little condos without experiencing any of the effects of destroying our lands and waters. That’s why we’re staying firm that no projects will go through, even though they keep telling our people, “They’re going to happen anyway, so either take the money now or you don't get it.” We’re saying that it’s not going to happen, because they don’t have consent.

That displays such a sense of entitlement from government and industry over Indigenous territory.

I’ve heard there are over 600 court cases that have been won by Indigenous people regarding lands. In the common law system a court’s decision is supposed to set a precedent so that the case doesn’t have to be proven again. Yet Indigenous people are still forced into the court systems to prove over and over that this is our land. The province and the federal government have not had to prove why they think they own these lands, even though they clearly don’t. Archaeological reports show that we’ve been here for thousands of years. Yet we continue to be dragged into court, to spend resources we don’t have, in a system that is always working against our people. It’s set up to benefit industry and government. It’s not there for the people.

What lessons have you learned that you would like to share with other land defenders?

Our biggest success has been alternative media. We are able to record and publicize all our interactions with the police and industry, and it has helped us to stay here as long as we have.

We also have the Delgamuukw v. BC court case that recognizes our land title. Nowhere in there does it make mention of band councils holding title to the territory; rather, it names our hereditary chief and house members as the ones with title.

Do you have any other advice for other land defence struggles that are taking place on Turtle Island right now?

Be open to people who are willing to help. Some people are impacted so strongly by racism that it is really hard for them to accept help from other people. But if we didn’t have the non-Indigenous folk here, the place wouldn’t have been as peaceful as it has been. If it was just Indigenous people here, police would have come full force, guns and all, and taken us out. But since we had non-Indigenous support they were reluctant to use overt violence; because, truthfully our people are not treated as human.

Do you have anything else you’d like to add before we end?

The battle we’re up against is not over yet. Once the snow melts, we’re probably going to be up against industry and police again. From my understanding, they are threatening to do court injunctions which usually cost a minimum of $500,000. They want to bankrupt us through the court system. It’s a lopsided system. The only way we can change that system is people power. People have to start making their voices heard. They can’t keep sitting back, thinking that what we’re doing out here is going to do the work for them. The more voices there are out there, the more we can make change.