MONTREAL—Undocumented migrants face significant barriers when it comes to accessing education, healthcare, food aid and other essential services in Canada. A new campaign to build “sanctuary cities” across the country, however, is making urban services more accessible to those without papers.

Being without papers impacts the day-to-day lives of migrants in countless ways, presenting a series of challenges that many Canadians would find hard to manage. Migrant justice groups won a significant victory on February 21, 2013, when the Toronto City Council passed what is known as the Access Without Fear motion. The motion has begun to dismantle some of the hurdles undocumented migrants face, and the effects are already visible. Syed Hussan, a member of No One Is Illegal-Toronto (NOII-Toronto), a collective that supported the motion, gives the example of funerals. “The city funds people's funerals. But many undocumented families are quite poor, and it costs at least $3,000 to die in Canada. [Undocumented migrants’] funerals were generally not funded by the city, but now [since the Sanctuary City motion was passed], we've heard of families who were able to access this funding...So there has been a shift in terms of direct experience.”

The motion stipulates that the city of Toronto will open up all its services for undocumented migrants and will advocate for changes to immigration policy at the provincial and federal levels of government. According to NOII-Toronto, this will be a historic step forward in the struggle for immigrant rights in Canada.

“What we're most excited about is that it's not just a commitment, but it actually has a detailed set of implementation protocols,” says Hussan. “In the actual motion, it says that the city has to do an internal audit to find out the ways that city services are being made inaccessible, and then do a training for the 15,000 city workers.”

The motion passed by a vast majority, with only three councillors out of 45 (five were absent) voting against it. Even to Hussan, the amount of support the motion received was surprising. “This just shows really implicitly that the work we've been doing in the city over the last 10 years has really made inroads into councillors at the municipal level,” says Hussan. “We never intended to go get a motion passed at the city level. That was never our plan. Our plan was this agency-by-agency, school-board-by-school-board, health-centre-by-health-centre approach. We wanted to really root this at all levels of the city.”

According to Hussan, the strategy of “sanctuary cities”—opening up city services to undocumented people—is beginning to spread across Canada. “We've now been contacted by people in nine cities across Canada who want to pass similar motions, two of which are actually city councillors themselves.”

Currently there are services and programs that many Canadian citizens and permanent residents take for granted but which non-status migrants have difficulty accessing. These include educational institutions, shelters, food banks and healthcare services. In recent years, Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) officials have shown up at such institutions to apprehend and deport undocumented migrants. For example, Briarpatch magazine reported that in 2009, immigration enforcement entered a community garden outside a Toronto food bank and deported one of its users.

The “access without fear” principle—one of the principles that a sanctuary city is based on—argues that undocumented migrants should be able to use these services without having to worry about being thrown in jail or sent back to their country of origin.

Working hand in hand with “access without fear” is the principle of “don't ask, don't tell,” which says that no one should need to show proof of immigration status when accessing a service.

The concept of sanctuary cities recognizes an important reality in Canada: there are an estimated 500,000 undocumented migrants living in the country, the vast majority of them in Toronto and Montreal, according to Solidarity Across Borders (SAB), a migrant justice network in Montreal. If authorities had the ability to fully enforce immigration law, those 500,000 people living undocumented in Canada could be subject to deportation. Migrant justice groups argue that the economies of urban centres would crumble if this happened: hardly anyone would be left to drive taxis, clean office buildings or work in restaurant kitchens, among other essential tasks carried out by migrant workers.

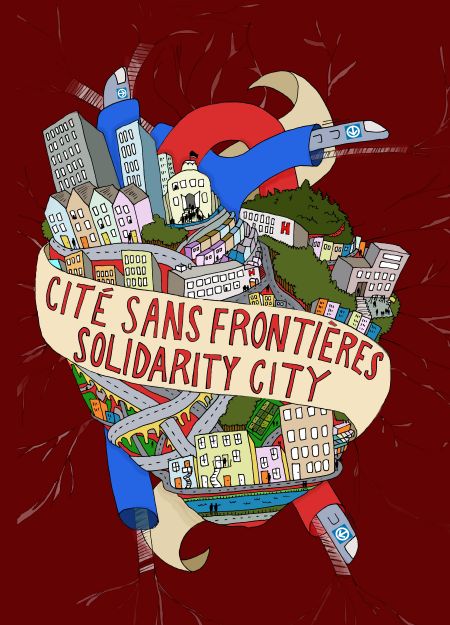

On the heels of the Sanctuary City motion in Toronto, community organizers with SAB are pushing towards a similar goal in Montreal. While no motion has been put forward at city council, SAB has been circulating a Solidarity City declaration since 2011. SAB is encouraging local service-provision agencies such as food banks, housing rights organizations and community centres who work with undocumented migrants to sign on. The declaration commits these organizations to endorse SAB's main demand of a regularization program for all non-status people, so that they can become permanent residents and stay in Canada. In the short term, the letter also asks organizations to ban CBSA authorities from their premises, allowing undocumented people to access their services without fear. So far, 25 different organizations have signed SAB's Solidarity City declaration, including student groups, labour unions and women's centres.

Work around granting access to a specific city service is being done with the larger goal of ensuring all undocumented migrants have the same rights as other Canadian citizens or permanent residents.

Emergency food-provision agencies are critical for undocumented people, says Leah Freedman, a member of the Food For All committee of SAB. “One of the main barriers is asking for identification documents in order to access food services—be that proof of income or proof of residency—because a lot of food banks only serve people in their catchment areas.”

“For a lot of people living without status in the city, there are many basic survival needs that need to be met,” says Freedman. “Often people without status are living in isolation and poverty. So just accessing basic services is really difficult.”

While Sanctuary City campaigns have a lot of wind in their sails in Toronto and Montreal, migrant justice organizers in other cities are adapting to their own local needs.

Harsha Walia, a writer and activist with NOII-Vancouver, explains that, historically, fewer migrants in Vancouver are without status than is the case in other large urban centres like Toronto and Montreal, although an increasing number face the problem of precarious status. For example, there are many temporary migrant workers who have overstayed their visas and risk deportation or are otherwise denied full access to services. “I think it's really important for people to realize the different terrains in different cities. That being said, there is no doubt that regularizing status for all migrants, ensuring full and equitable access to services, and a broader systemic conversation about displacement is necessary everywhere,” says Walia.

As an example of migrant justice campaigns taking different forms across the country, NOII-Vancouver has put much of its organizing in recent years towards building links of solidarity between migrant and Indigenous communities. Some examples of this in recent years have included mobilizing migrant communities in support of the Indigenous-led opposition to the Vancouver Winter Olympics in 2010, as well as organizing demonstrations against oil pipeline development through Indigenous territories.

Despite the Sanctuary City victory in Toronto, and with momentum growing in Montreal and elsewhere, the migrant justice organizers The Dominion spoke to know their work is far from done.

NOII-Toronto used its May Day march to ramp up the momentum behind the Sanctuary City motion but also to denounce pieces of federal anti-immigrant legislation. Amongst many regressive measures, Bill C-31, officially known as the “Protecting Canada's Immigration System Act,” has introduced mandatory detention for many asylum seekers.

With another two years of a Conservative majority government, similar anti-immigrant measures could still come forward. However, while federal legislation is moving Canada further away from an amnesty program for undocumented migrants, activists are hoping to build regularization from the ground up with Sanctuary Cities.

Aaron Lakoff is a radio journalist, DJ and community organizer living in Montreal, trying to map the constellations between reggae, soul and a liberated world.