HALIFAX—Bills C-45 and C-38, the Harper government's recent, and massive, omnibus bills, have laid waste to legislation relevant to the futures of all Canadians. But from the wreckage of the Indian Act, the Environment Act, the Canadian Labour Code and the Navigable Waters Protection Act has sprung the potential of alliances between groups that might otherwise not venture much beyond the concerns of their respective pet causes.

With alliances, however, comes the real risk that, like so many tectonic plates, the concerns and needs of certain groups stand to be ground down under the agendas of the very partners they would ally themselves with. Not all partners will have come to the table with the same social capital or collective experiences. Yet on paper—and in so many photo shoots—messages of solidarity and handshakes have recently suggested flawless coalitions between various willing partners.

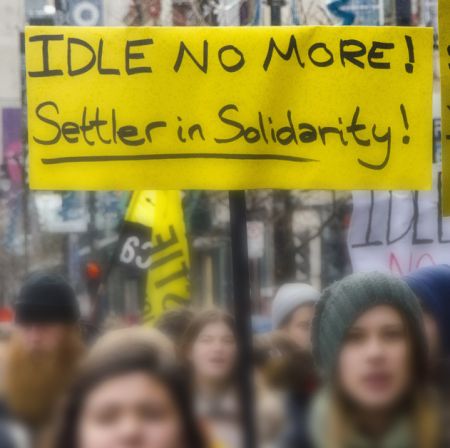

Take the case of Idle No More. In reaction to Bill C-45, and quick out of the gate in mid-December, the Indigenous-led movement appeared at first to be a master class in motion on effective grassroots organizing. From highway and railway blockades, to shopping mall round dances, to the focal point of chief Theresa Spence's hunger strike, the movement captured the attention and efforts of Indigenous peoples aligned against the Harper government's violation of “treaties, Indigenous sovereignty and subsequently environmental protections of land and water,” as organizers explained it on the Idle No More website.

Outpourings of support and solidarity towards the movement came from all manner of individuals and organizations, including all of Canada's major unions. By late December 2012, the executive councils and/or presidents of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (approx. 54,000 members), the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) (180,000+ members), the Canadian Auto Workers (200,000 active members), the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers (CEP) (120,000 members), the Canadian Union of Public Employees (618,000 members) and the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), among others, had all penned letters of solidarity with Idle No More and demanded that Stephen Harper meet with the hunger-striking Spence.

Representing several hundred thousand unionized workers across Canada, and facing a concerted attack of their own from the Harper government, it seemed like the moment of a lifetime. Would the PSAC follow suit and walk out on their Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development-unionized offices? Would the CEP shut down the tar sands? Would chants of “Solidarity forever” become the roar of a grassroots movement among Canada's non-Indigenous population?

Not quite yet, and this may well be indicative of one of the weaknesses of today's 'established' labour movement, as opposed to a grassroots movement like Idle No More.

“The labour movement, we have strengths and weaknesses,” says Tony Tracy, Atlantic Region Representative for the CLC. “People don't join the labour movement because they have an ideological position against the boss. They join the labour movement because, generally speaking, they got a job and that job happens to be unionized. So we don't pick our members, our employers do...We have to win those workers over, workplace by workplace by workplace.”

In other words, an alliance on paper with a union executive is not necessarily a partnership with the membership of a 100,000-strong organization. Indeed, while the push for good jobs and a living wage is certainly important, the primacy of jobs above all else may well pit unions against potential allies, especially those who might espouse longer-term goals that will require material sacrifice from the present generation so that future generations might thrive.

"If unions truly understood treaty, they'd support First Nations in using their treaty powers to create a law against the Harper government—even if it costs jobs," says treaty scholar Kevin Christmas, from Membertou First Nation. “To me, that would be a measure of progress. But that won't occur, because everything is wrapped up. Where are all the pension funds? Where are all those millions of dollars invested? If you start looking at the whole infrastructure... It's aligned towards a certain outcome.”

Christmas and others within grassroots Indigenous communities see the act of making alliances with non-Indigenous groups as burying the movement's most powerful card—legal treaty and title to the land—underneath a pile of certainly valid, yet legally toothless, concerns.

“The alliance is an alliance against our right to decide,” says Christmas. “The alliance is an alliance against treaty. It's an alliance against our standing as a partner. It has to get lost, because nobody in the alliance can make a decision by themselves.”

Within an alliance, suggests Christmas, consensus before action is necessary, whereas within the Indigenous community decisions can be reached independently. Not only this, but non-Indigenous partner groups are—unless committed to dismantling the state—part of the state themselves. And history has taught that the state, whether known as the Crown or as Canada, is anything but an upstanding and trustworthy partner.

“We will always be a willing partner dealing justly with an unwilling partner who is dangerous,” says Christmas. “When you buy into that alliance against you, which is the whole of the Canadian decision-making matrix including all the unionized employees and employers and public servants and regulators and provincial legislators...all of that Settler infrastructure is really an unwilling alliance against our self-determination.”

Despite the risk of getting lost in the mix, it appears that alliances are forging ahead. On January 28, 2013—which happened to be an Idle No More 'national day of action'—a group known as 'Common Causes' was launched. At the Halifax launch, there was some displeasure amongst the crowd who, for the most part, had gathered for a march to commemorate Indigenous survivors of Canadian residential schools. In what bordered on poor taste, numerous marchers were arbitrarily handed Common Causes placards to carry and be photographed with.

The group itself is headed by the Council of Canadians, which, except for a message of solidarity from the Idle No More website, is currently the only public face of this alliance. According to Angela Giles, Atlantic Regional Organizer for the Council of Canadians, the anonymity of partners—47 as of last September—is the result of some members being charities which currently receive funding from the Harper government.

“[Some of the groups involved] are not comfortable saying 'Yes, I'm going to be part of Common Causes, who's fighting against the Harper agenda,' when in fact that would be biting the hand that feeds them,” says Giles. “So we never created a list...but there are a diversity of groups who are involved and they include groups that represent workers, the poor, students, First Nations, women, environmentalists, farmers, educators and human rights and social justice advocates, immigrants and refugees, writers and artists, scientists, aid and development workers and on and on.”

It is a packed—albeit anonymous—house, to be sure; and one which is admittedly entrenched in the workings of the state. Indigenous treaty rights, conspicuously, do not appear among the key 'critical areas' listed on its website.

Lacking a general groundswell of membership interest, however, does not necessarily mean that non-Indigenous partners are completely without their strengths. Canadian unions, in particular, have money at their disposal with which they have helped fund grassroots initiatives both within Canada and abroad. But while the opening of union coffers earmarked for solidarity work might be well-intentioned, funding a grassroots movement also holds within it the seeds of co-option.

As a bureaucratic organization, a union, when distributing funds to a grassroots movement, will necessarily seek out a leader amongst the movement. It may, in effect, bureaucratize a movement where no bureaucracy is desired. When members of a grassroots movement get funded, that small group becomes suddenly different than the grassroots. If the people whom a union chooses to fund have an agenda different from other components of the movement, those in opposition are weakened due to a lack of similar funding.

“It's kind of self-selecting in some ways, because not all folks would think to reach out to us,” explains Tracy. “It's not everybody in any movement who, the first thought that would come into their heads would be 'We've got to call the unions.' But if somebody reaches out to us and they seem genuine, then we want to treat them genuinely.”

The bureaucracy of funding has now potentially polarized the movement, with the designated leader now becoming a gatekeeper to money. The individuals who are funded are also now more likely to be approached by interest groups, which in the case of Idle No More might mean the Assembly of First Nations Chiefs and similar groups, which might not have the best interests of the grassroots people at heart.

Without extreme diligence, segments and tactics of the movement can be marginalized, while the well-funded portion of the movement presents its mandate and tactics as being the only ones representative of, or endorsed by, the movement. Thus, while Christmas and other grassroots people across the country are sounding alarm bells over the myriad comprehensive land claims currently being negotiated towards what is perceived to be a 'final solution' to the issue of treaty rights, the very chiefs involved at the negotiating tables have been welcomed as part of the public face of Idle No More. Alliances with labour, environmental and all manner of non-Indigenous activist groups, may be well-intentioned, but they remain alliances with the “unwilling partner”: the state.

“You try to rally, in Indian Country, i.e., Idle No More. You try to get the grassroots to come together, and all the chiefs who are participating in the comprehensive claims policies and negotiation at self-government tables, and who are formally involved with the tripartite levels of government, are actually part of the unwilling partnership,” says Christmas. “So the only benefit that they can get is what the unwilling partnership is willing to take.

“What's an adequate response to an unwilling partner? Because you know that his friends are going to be your enemies. And his alliances are going to be against you. And his enemies need him. It's like an atheist needing God. The unions, the only strategy they're offering is one that's destructive. The only thing that's on the table is not economic development, it's environmental destruction and degradation.”

Miles Howe is a member of the Halifax Media Co-op and an editor with The Dominion.