Kenora, ON—With Winnipeg’s drinking water under threat from a proposed crude oil pipeline, TransCanada’s consultation process is leaving residents and activists with more questions than answers.

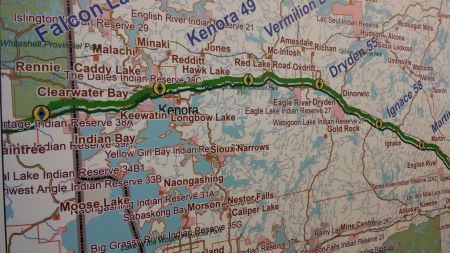

In a project called “Energy East,” the TransCanada Corporation plans to convert an existing natural gas pipeline to transport up to 1.1 million barrels of crude oil from the tar sands, through Ontario, to refineries in eastern Canada.

Winnipeg-based environmental groups and members of Idle No More are concerned about how close the proposed pipeline will run to Shoal Lake, ON, the source of Winnipeg’s drinking water. A major concern raised by activists is the possibility of a spill so close to the water supply.

Idle No More activist Crystal Greene drove three hours from Winnipeg to attend an Energy East open house in Kenora, ON, which lies 50 kilometres east of Shoal Lake.

“As an Anishnabe-kwe, I see that it’s my role to protect the water, it’s the role of the women to protect the water,” Greene told The Dominion at the September 16, 2013, open house. “I feel like it’s my responsibility to speak up for that lake.”

Shoal Lake is not new to water issues. Residents of Shoal Lake #39 and #40 First Nations have been under a boil water advisory for over 12 years. The community must haul in their drinking water, at a cost of almost a quarter of a million dollars a year. When the Winnipeg aqueduct was built at Shoal Lake nearly a century ago, it cut across a burial ground and split part of the community, now known as Shoal Lake #40, into an island.

The open house in Kenora was staffed by over a dozen TransCanada employees and an Aboriginal relations firm. Staff answered questions and guided visitors through an exhibit, but were unable to provide concrete information about how close the pipeline will run to Shoal Lake. The exhibit’s detailed satellite maps of the pipeline’s path omitted the area west of Kenora to the Manitoba–Ontario border, where Shoal Lake lies. The non-profit advocacy group Council of Canadians lists Winnipeg and Shoal Lake #40 First Nation as being on or near the existing natural gas mainline.

Several Kenora-area activists who came to hand out leaflets about environmental issues were asked to leave the building. Red Lake, ON, resident Lawrence Angeconeb spoke to The Dominion in the parking lot while giving out leaflets. Angeconeb explained that if a leak were to occur in the existing natural gas pipeline, “the gas goes up, rather than down. With oil, if it ruptures, it goes down: into the soil, into the rivers.”

Climate and energy campaigner for the Council of Canadians Maryam Adrangi pointed out that the natural gas pipeline that TransCanada plans to convert for shipping crude is an old pipeline that was originally constructed without the consent of affected communities. “Communities on the ground are still not given the right to ultimately say ‘no,’ even though they are the ones who would have to face the true costs of a pipeline rupture,” she wrote in an email to The Dominion.

The effects of such a rupture could be devastating. In 2010, for example, a pipeline transporting diluted bitumen from the tar sands spilled into Michigan’s Kalamazoo River. Three years later, the oil is still being cleaned up. The diluting agent in the bitumen, necessary for pipeline transportation, vaporized during the spill and the remaining oil sank to the bottom of the river.

Adrangi added that the pipeline enables the expansion of “an already dirty industry which is severely impacting communities living downstream.”

Some Indigenous activists are concerned that their treaty rights, which should protect their land and communities, have been eroded by federal legislation passed last winter. The Idle No More movement took off last October, building on widespread opposition to Bill C-45.

The bill, passed in December 2012, changed environmental protection legislation such as the Navigation Protection Act and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act. Since the changes, pipeline and power line companies are no longer required to demonstrate that their projects will not damage waterways, unless the waterway is on a list prepared by the transportation minister. Idle No More has claimed that this effectively removes protections for the vast majority of Canadian lakes and rivers.

Bill C-45 was accompanied by other omnibus bills, including Bill C-428 and Bill S-212. Together, the bills weakened environmental regulations, changed how appropriations of reserve land occur and decreased federal responsibility to protect waterways.

Greene said that these interlocking pieces of legislation clear the way for development and resource exploitation by eroding Indigenous land rights, which she called the “security net to protecting this land for people of all nations.”

Whether the new legislation has affected TransCanada’s Energy East pipeline consultation process is unclear. Although some media coverage has framed TransCanada’s open house events such as the one in Kenora as consultations, activists say that there was no meaningful dialogue or process to give input.

TransCanada spokesperson Philippe Cannon told The Dominion that the company is in the process of “stakeholder engagement and gathering information” before the company files for approval from the National Energy Board.

TransCanada has delayed filing its application with the National Energy Board until 2014, which may delay its anticipated start date for shipping crude oil. Once the filing is complete, the approval process could take between 18 and 24 months. The National Energy Board is currently conducting hearings on a second pipeline moving oil from western Canada, Enbridge’s Line 9B.

Cannon said that TransCanada’s stakeholder engagement strategy is to organize open houses, meet with landowners, and gather comments through TransCanada’s website. He said the public response to the project has been positive.

Some open houses have seen visible opposition, however, such as the one in North Bay, ON, where 50 people protested the project wearing satirical “SaveCanada” shirts in imitation of TransCanada employees’ attire.

When pressed, Cannon was unable to confirm whether TransCanada’s “stakeholder engagement strategy” represented the entirety of its consultation process. The National Energy Board’s website lists a number of acceptable consultation methods, including open house meetings, radio spots, and questionnaires. The Dominion spoke to about ten concerned area residents who expressed criticism of the open house format, which was not designed to invite residents’ opinions, especially critical ones.

Kenora resident Teika Newton followed the lead of North Bay activists and sported a “SaveCanada” T-shirt at the open house, where The Dominion interviewed her. “[The open house was] presented in a format where community discussion is not encouraged,” she said. “You’re having a lot of one-on-one conversations with people, each person coming in and getting a different piece of the puzzle.”

TransCanada did not organize an open house in Winnipeg, but held one in the community of Île-des-Chênes, 25 kilometres outside the city of Winnipeg. Greene said that the distance made the open house inaccessible to many Winnipeg residents.

Newton was concerned that even if the National Energy Board were to disapprove the project in response to community opposition, “the federal government has the authority to override decisions made by the NEB if it is in the national best interest.”

The Council of Canadians shares similar concerns. Bill C-45 and other omnibus bills passed by the Conservative government have sought to streamline approval processes for energy projects. Adrangi said this means shortening timelines and creating barriers to submitting complaints, such as providing “ten-page documents that interested participants need to fill out.”

In addition to environmental and safety issues along the pipeline itself, activists like Lawrence Angeconeb are concerned about the First Nations communities in Alberta, such as Fort Chipewyan and Fort MacKay, that are directly affected by tar sands production.

Angeconeb said his personal mission is “to get everyone in Treaty 3 and the First Nations communities that surround Kenora to oppose the pipeline as an act of solidarity for the First Nations communities that are affected directly” by the tar sands.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples prescribes a protocol of free, prior, and informed consent for projects that impact Indigenous lands and peoples. Adrangi said that the development of the tar sands, as well as the original natural gas pipeline for Energy East, violated those protocols. “Local people should be agents of local governance, and Indigenous peoples have been and are still being denied that right,” she said.

Outside the open house, Angeconeb added, “They’re saying that they’re approaching First Nations and they’re not really saying who, and that’s just how secretive this whole process may turn out to be.”

The role of Indigenous people in environmental approval processes is one of the many issues that continue to be raised by the Idle No More movement. Over the summer, several members of Idle No More Winnipeg initiated “Water Wednesdays,” a weekly event that connected INM supporters with local environmental organizations to strategize and share stories.

“When they unveiled their plans for the west-to-east pipeline on August 1, I knew that we had to start informing each other of this,” said Greene. “As Indigenous peoples, our entire existence and identity and rights are connected to the land and the water.”

Greene said that the role of treaty rights in protecting land and water is what makes the Idle No More movement appeal to Indigenous and non-Indigenous people alike. “Indigenous rights are our last resort to protecting the land, the air, the water,” she said. “If it wasn’t for the land and the water, there would be no life.”

Shelagh Pizey-Allen lives in Winnipeg.