MONTREAL—On a January morning in 1963, residents of the island nation of Barbados heard a deafening thud. The sound echoed across the country, and white smoke soon billowed from the site of the detonation, saturating the sky with the smell of gunpowder. One of the largest guns in the US arsenal, which had been brought to the island only a few months prior, had just sent its unusual payload hurtling into the upper atmosphere: a 200-pound vehicle known as the Martlet.

"Martlet" is the name of the mythical bird that is found on McGill University's crest and might seem a relatively innocuous school mascot. But the 200-pound vehicle to which it lent its name leads us into McGill's long and little-known history of weapons research. The extent of this research, and its ongoing nature, has recently been revealed by Access to Information (ATI) requests filed by The Dominion and by Demilitarize McGill, a student-led campaign to disrupt defence research on campus. (Download the Freedom of Information Act documents here and here.)

According to a 2010 grant application accessed by the group, McGill prides itself on participating in “state of the art research in the fields of ballistic protection, Shock Wave physics, and detonics” and on being a valued partner in “state-of-the-art [research] in autonomous localization, navigation and mapping for unmanned vehicles.”

The university’s current enthusiasm for military technology can be traced back more than 50 years, to a man named Gerald Bull. Bull’s life story reads like a John le Carré novel. He was born in North Bay, ON, to an affluent family that lost most of its wealth in the Great Depression of the 1930s. While studying at a private college in Kingston, Bull was invited to attend the University of Toronto, where he would find his calling in the fledgling department of aeronautics. His passion for engineering and aerospace more than made up for an initially unremarkable transcript: Bull would become the youngest PhD graduate in the university's history.

By the early 1950s, Bull was working for the Canadian military. He envisioned a world in which artillery fire, not rockets, would be the most widely used method of reaching space. Drawing inspiration from the Paris Gun, a 34-metre German railroad gun used to shell Paris during the First World War, he began working on what was called the High Altitude Research Project, or HARP. Initially funded almost entirely by a $200,000 loan from McGill University, HARP was born for the purpose of launching projectiles—useful for increasing the effectiveness of ballistic missiles—into space.

Government money soon began pouring in, and with the support of the US Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory, HARP acquired a 16-inch gun and a $750,000 radar station. Although the Martlet-launched vehicles provided the US military with valuable data on upper atmospheric weather, the project lost most of its American funding after the Vietnam War.

Bull found himself in desperate financial straits. His efforts to sell his work to the highest bidder—first to Iran and Israel, and later more controversially to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq—would eventually lead to his assassination in a Brussels apartment, most likely by Israeli agents.

But his legacy is still alive. Though the 16-inch gun is long gone, and Bull’s dream of firing satellites into space has diminished, research continues at McGill University where Bull was once a professor. And although the experiments of McGill's Shock Wave Physics Group are not as lofty as Bull's were, many still lead to technical breakthroughs for the Canadian military.

David Frost and Andrew J. Higgins are two McGill professors whose current work benefits the Canadian Forces, particularly in combat situations. According to ATI-obtained documents, Frost and Higgins are conducting research to “develop new field-responsive armours [that] would be invaluable to the Canadian Forces, as well as to other security personnel.” Their work involves the testing of what is called "shear thickening fluid," a material whose viscosity increases when strain is applied—the basis for a lightweight fabric that could become harder and more difficult to penetrate if struck by a bullet.

This research is part of an overall effort of Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC), an agency of the Canadian Department of National Defence, to improve the quality of fabrics in armoured vests and other protective gear such as those used by Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan.

Other research carried out by Frost and his colleagues involved more offensive weaponry. One of Frost's papers, published in 2001, contains information pertinent to the development of thermobaric bombs, fuel-air explosives deemed more destructive than conventional explosives because of their longer-lasting blast waves. This paper was later cited in US Air Force research to develop more efficient fragmentation weapons and, according to an abstract, to increase the “lethality” of blasts by “focusing more of the available energy on [a] target.”

More recent grant applications accessed through ATI requests suggest that Frost is still involved in the study of explosives. In 2008, Frost sought funding for research on improving “the performance of commercial explosives.” This research mainly focused on predicting explosive blasts to facilitate mining operations, but some of Frost’s other grant applications also had potential for military use.

One specifically mentions protecting soldiers from the effects of “accidental or deliberate explosions.” In another, Frost proposes to investigate how gas—specifically, the “combustion of large-scale dust clouds of inorganic solid fuels,” such as light metals and sulfur—might neutralize chemical agents used against Canadian soldiers in combat.

In 2010, McGill’s senate passed a policy on research conduct that specifically omitted ethical regulations for military research. Prior to the decision, Demilitarize McGill had been calling for the creation of a formalized system of approval that would give senior administrators the oversight of any research with “harmful potential.”

“Having these things reviewed is fine, but you have to look at what the cost is, and if it’s delayed, that might be a graduate student not getting a stipend,” Higgins said in an interview with The Dominion. In the early 2000s, Higgins had three contracts from defence organizations under review for approval by McGill’s board of governors, the university’s highest governing body.

“In all cases the researchers have complete freedom to decide if they want to engage in a research collaboration project or a service contract,” wrote Rose Goldstein, the university's Vice-Principal of Research and International Relations, in an email to The Dominion.

The Shock Wave Physics Group is only one of McGill’s laboratories that have been conducting defence research in recent years. Researchers at the university’s Aerospace Mechatronics Lab are also helping the Canadian Forces develop drone technology to be used in combat. Drones, or unmanned aerial systems (UAS), are aircraft without a human pilot on board. They can either be remotely controlled, or guided through autonomous navigation technology.

The DRDC’s foray into robotics began during the Cold War. In the late '70s, research conducted by the Autonomous Intelligent Systems Section (AISS) of DRDC focused primarily on tele-operation robotics, vehicles remotely controlled by humans. By the early 2000s, remote operation was giving way to autonomous technology, as AISS began shifting its attention to systems that could operate entirely on their own.

The DRDC's stated aim, according to its 2004 technical report, was to assemble a fleet of unmanned vehicles that could “operate and interact” with one another in combat. The development of a strategy, or a common software architecture, that integrates different vehicles, would allow the Canadian Forces to harmonize the operations of unmanned air, ground and marine systems. "Systems" here is a military term for vehicles such as drones, armoured cars and submarines.

For DRDC, the battlefields of the future would be shaped by robotic collective intelligence. Autonomous decision-making would be based on the constant collection of data and exchange of information between the various independent unmanned systems and soldiers on the ground. For example, drones would be able to share their bird’s-eye view and mapping capabilities with other unmanned vehicles and soldiers on the ground or at sea.

The Department of National Defence has been preparing for this vision of battlespace by funnelling research from industry and academia to military branches. To this end, the Department’s Research and Development agency has been fostering intimate ties with universities, including their “academic partners from McGill University,” according to a paper outlining DRDC’s approach to unmanned operations.

Since 2011, McGill has received more than $1 million in Department of National Defence contracts. Research on unmanned systems is so prevalent on the campus that the university boasts its own UAS research group. The group was assembled over the course of the last two decades by Inna Sharf, a professor of mechanical engineering.

Sharf has developed an extensive relation with the DRDC-Suffield Research Centre in southern Alberta, which specializes in autonomous systems for ground and air. According to her resume, DRDC-Suffield has awarded Sharf three defence research contracts on unmanned systems since 2004 at a value of over $500,000.

In spite of the increasing application of unmanned systems for military, law enforcement, surveillance and border patrol purposes, some of the research conducted at McGill is being carried out for peaceful use. David Bird, a professor of wildlife biology at McGill’s Macdonald Campus, is a strong proponent of the scientific application of unmanned systems. Bird and one of his graduate students have conducted a wildlife preservation project in partnership with Canadian drone company Draganfly.

Yet Draganfly's drones were also used to conduct police surveillance on an Indigenous blockade of CN Rail’s tracks near Tyendinaga, ON, in early March of this year. The blockade, which called for a national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women, stopped traffic between Montreal and Toronto. The Ontario Provincial Police took to Twitter to defend its use of drones: “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles are an economical way to take pictures. It is a tool used in investigations.”

It seems unlikely that the Department of National Defence would heavily fund research in autonomous technologies in order to satisfy its soldiers’ bird-watching hobbies. In fact, the military potential of research is explicit in the language of the funding contracts for which the work is performed.

“If the work is being sponsored by the research department, you will find in the language [of the] contract how it is relevant to defence. They are not a philanthropic organization. They are funding this, they have some programmatic mandate,” Higgins acknowledged.

Sharf’s latest DRDC-funded project, according to documents obtained by The Dominion, is titled “Autonomous Support for UAVs” and valued at over $380,000. The project intends to provide autonomous unmanned vehicles (UAVs), such as drones, with the ability to land autonomously. Drones capable of this behaviour would be able to conduct surveillance missions more efficiently, and their operators would see their workload diminished.

In an interview with The Dominion and The McGill Daily, Sharf denied the military applications of her research. “My work focuses on making landing and taking off for [unmanned aerial] vehicles more autonomous,” she told The Dominion, adding that “there’s many applications: fire surveillance, harvest surveillance.”

Yet the contracting authority at DRDC-Suffield makes it clear that the objective of Sharf’s project is to improve soldiers’ effectiveness in combat. The contract mentions that the research would ultimately “provide battle-space awareness” in combat operations and act as a “force multiplier” for soldiers on the ground. In other words, the technology developed at McGill would allow for the rapid crafting of maps in unknown environments and then allow for extended surveillance and data collection. Unmanned aerial systems equipped with this technology would “track and intercept” moving targets. This capacity, supplemented with facial-recognition technology, would allow the drone to match faces against police records or eventually an enemy kill list.

Under third-party contracts with DRDC, the federal government owns intellectual-property rights to the work performed at McGill. Sharf and the team under her supervision do not own the technology and may use the results of their research only for publication and academic purposes.

Likewise, DRDC-Suffield has no say in—or responsibility for—how its technology will be applied. The Canadian military is solely responsible for choosing how to apply the research, for whatever purposes it sees fit.

McGill is not unique in its involvement in weapons development. The Department of National Defence funds research at dozens of universities across Canada. In fact, Queen's University banked $3 million for a single contract in 2012, almost three times what McGill received in three years. It would seem that McGill’s funding, for all the persistence it took to uncover it, is just a drop in the bucket.

Nicolas Quiazua is a freelance journalist and documentary filmmaker actively involved in supporting the Demilitarize McGill campaign. Laurent Bastien Corbeil is a freelance journalist based in Montreal.

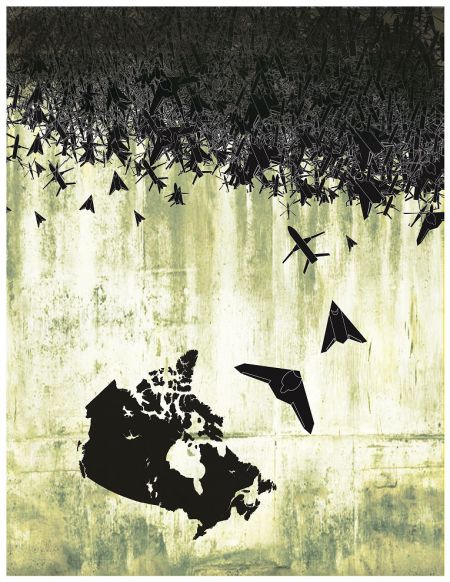

Cover artist: Tiaré Jung is a visual storyteller, singer-songwriter, and facilitator for healthier, more inclusive communities, living in unceded Coast Salish Territories. See more of Tiaré's work at tee.ah.ray.tumblr.com.

Both of the FOIA documents (Freedom of Information Act) documents referenced in this article can be downloaded below.