BENITO JUÁREZ, MEXICO—It was a day he'll never forget, but it began like any other for Erick Solorio Solís, an engineering senior at the Autonomous University of Chihuahua (UACh) in Chihuahua, Mexico. He rolled out of bed on Monday, October 22, 2012, and stepped into the warm morning air that graces Chihuahua City through the fall. He had a bite to eat, and took a quick call from his parents, who were heading to the city to visit him and his brothers later that day. Solorio, a tall young man with inquisitive eyebrows and a trace of a beard, went to school and sat through three hours of classes. He recalls that he left campus around noon. With his two brothers, then-21-year-old Solorio spent the next couple of hours at home, waiting for his parents to arrive.

After the morning phone call with their son, Solorio’s parents hopped in their pickup truck and pulled out of Benito Juárez, a rural town a couple hours south of the US border, where the Solorio family has farmed for three generations. Solorio’s mother was due for a check-up in Chihuahua, and his father planned to take advantage of the outing to run a few errands.

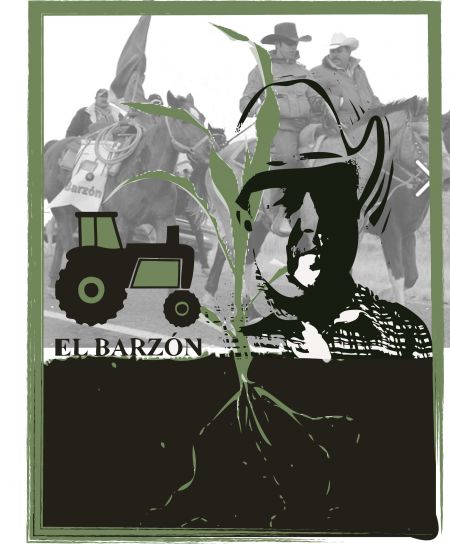

Around 2:00 pm, Solorio’s elder brother got a phone call from a local police official. The man said their parents had been involved in an accident. Erick called his uncle, who said his parents had been caught in the middle of a firefight. The brothers went to the offices of El Barzón, a farmers' rights group their father was involved in, to see what was happening. It was then they found out that their parents had been murdered.

“The first thing we thought was that it was people from our town, the people from the mine,” said Solorio in an interview with The Dominion in Chihuahua City. “The jealousy was too much, the hatred they had towards [my father] because he demonstrated, using facts, that the mine [would be] bad.”

Ismael Solorio Urrutia and Manuela Solís Contreras breathed their last breaths seated inside their truck, which was parked beside the highway leading out of the city of Cuautémoc.

According to video footage acquired as part of the investigation into the murder, Ismael pulled his pickup off the road, and turned the car around as if to talk to the driver of a car that had pulled in behind him. As the killer approached, Ismael pulled 160 pesos (about $13) out of his wallet as if planning to pay him. He was still clasping the bills when his body was found.

When I asked Martin Solís Bustamante, a Barzón activist and lifelong friend of the family, how exactly they died, he got up from his chair and walked around behind me, pressing two fingers to my lower skull. Two shots passed through Ismael’s skull and lodged themselves in Manuela’s breast and shoulder, killing her.

Their killings are the first of opponents to Canadian mining in Mexico's northern Chihuahua state, where, by 2011, mining companies were granted concessions to 54 per cent of the land.

The double murder shocked the people of Benito Juárez, a desert town, population about 12,000. Benito Juárez spreads out from a small central park, where vendors sell ice cream and burritos and elderly men rest on benches in the shade. After a few blocks, the paved roads leaving the park turn into dusty gravel roads, which lead for kilometres into a harsh desert. Water flows from a reservoir at the foot of the Carmen River through a small canal, providing farmers with the raw material for cattle ranching, chilli growing and cotton harvesting, the economic mainstays of the area. Benito Juárez is also an ejido, which means that the 53,000 hectares of land there is collectively owned and farmed by about 400 families.

The road out to where MAG Silver—a Vancouver-based mining exploration firm—was drilling core samples cuts through sun-baked desert plains, flanked by mountains in all directions, the stark landscape interrupted only by chaparral bush and spindly spikes of ocotillo. Without irrigation, little survives here, and securing water in the desert is no small feat. In Benito Juárez, the effort to ensure the survival of the local economy and a way of life based around family and farm is multi-generational and involves hundreds of residents.

Ismael Solorio and Martin Solís, for instance, studied together at an agricultural school in Juárez. Returning to the ejido in the early 1980s, they got their start in activism, organizing in defense of predatory banking practices after the peso was devalued in 1987, and using direct action to help improve the lives of the ejido's members.

Later, Solorio and Solís helped form the Barzón movement (a barzón is the yoke-ring on a plough), whose members captured the attention of the nation when they entered the country’s national congress on horseback after riding 54 days from the US-Mexico border crossing in Ciudad Juárez to Mexico City. The bold tactics of the Barzonistas brought back memories of Mexican revolutionaries at the turn of the 20th century. They successfully forced the first change in the rural budget anyone can remember, and later secured electricity subsidies for rural farmers whose livelihoods were under threat following the unequal terms of the North America Free Trade Agreement.

In the last years of his life, Ismael Solorio, who was known to his friends as “Chops,” continued to grow chilli peppers and raise cattle, while devoting his spare time to water and mining issues in the region. A far cry from a full-time activist, Solorio devoted most of his time to working on the land, speaking out when he felt outside forces threatened the future of his community.

First was a host of off-the-books deep wells drilled by Mennonite farmers which sapped the Carmen River of the flow that had long provided water for farming in Benito Juárez and other desert communities. Then there was MAG Silver, which was carrying out a controversial drilling program at its "Cinco de Mayo" project to explore for silver, gold, copper, molybdenum and tungsten in lands locals claim are communal.

Ismael and and his wife Manuela, a primary school teacher and ardent supporter of her husband’s activism, had faced-off against many powerful forces: banks, governments, and wealthy well drillers. But something was different this time. Tensions rose quickly; the conflict heated up, and in a matter of months Manuela and Ismael were dead. In the months before he was killed, Solorio denounced death threats he received and aggression by people he said were paid by the mining company, and demanded the government provide protection. His requests were ignored.

“Since 1985 we have been involved in different actions and mobilizations as part of social resistance,” said Solís, who spoke to The Dominion from El Barzón’s Chihuahua City headquarters. “We always confronted the government, and we had never confronted organized crime,” said Solís, speaking confidently and steadily.

The decision to kill Manuela and Ismael didn’t come from the head of a drug cartel, Solís emphasized. Far from drug lords, the killer and his accomplices were local men who had been involved in carrying out the dirty work for a crime group known as the Juárez Cartel: “Hit men, armed men, people who previously had threatened Ismael related to the actions he was taking against the mining company,” said Solís.

Dozens of statements collected by police in the months following the murders make it plain that MAG Silver’s exploration program was a source of conflict in Benito Juárez. Testimonies included in the state investigation of the murders, reviewed by The Dominion, include references to men claiming to be plainclothes federal police without badges or a legitimate arrest warrent threatening Ismael, and fights between mine exploration workers and those who didn’t support the mining project. A geologist working for the company was also questioned.

The man believed to be Solorio's assassin was murdered by police on January 19, 2013, but Solorio's friends and family refuse to stop their quest for accountability. “We have maintained that justice must be done and the other material authors must be detained, but so must the intellectual authors of this crime,” said Solís.

Today, instead of working in the fields or sitting around a table talking with friends and family, Manuela and Ismael are gone. Their bodies are buried under the desert earth they once farmed. Their names, along with dozens of others, grace a rebel monument erected to remember victims of violence in Chihuahua state, among them other activists, Indigenous community members and young women.

Chihuahua is considered by some to be the most dangerous state in Mexico, with more than 4,480 murders in 2011, the last year for which there are official statistics. The violence isn’t contained in Ciudad Juárez, the notorious border city that until recently was considered the murder capital of the world.

Saul Reyes Salazar, an activist from the Juárez Valley in northern Chihuahua, who fled to Texas with approximately 30 members of his family following the murders of four of his siblings and his sister-in-law, compared killings of activists in Chihuahua with a kind of social cleansing. “We’re not the only ones who have suffered this tragedy,” he said in an interview with The Dominion in an El Paso cafe. “In Chihuahua, there have been more than 40 social, environmental and human rights activists who have been murdered, I consider it like a cleansing…an ideological cleansing.”

Previous conflicts sparked by irresponsible mining in the state include the case of Pan American Silver in the town of Madera, as previously reported in The Dominion.

As October’s double murder echoed through anti-mining networks throughout Mexico, Manuela and Ismael’s names were added to a growing list that already included Mariano Abarca, killed in Chiapas by hitmen connected to Blackfire, a Calgary-owned mining company, in November 2010, and Bernardo Vásquez, murdered March 15, 2012, because of his activism against Vancouver-based Fortuna Silver.

MAG Silver has denied its operations have anything to do with the murders. "MAG and our Mexican consulting contractor, El Cascabel, had absolutely no involvement in the tragic event," Dan MacInnis, the CEO of MAG Silver, wrote in an email to The Dominion. Instead, MacInnis earlier claimed, "We are victims broadsided by a long-standing community dispute.”

The police investigation into the murders back up the fact that it was a community dispute that triggered acts of violence ending in the murder of Ismael and Manuela. But it also makes clear that the prospect of well paying jobs MAG Silver brought to Benito Juarez was at the heart of the dispute.

“That’s what is so painful for us, you know, the fact that members of the community handed over Ismael and Manuelita, that’s something we know, that here in Benito Juárez the deal was made and everything so that they would be killed,” said Siria Leticia Solís Solís, a long time resident of the community and a member of the Barzón, in an interview with The Dominion. “We blocked the company, and because of that people are being killed,” she said.

Since the killings, mining exploration work in the community has stopped, but tensions haven’t fallen off. In an assembly where more than half the members were present, the ejido of Benito Juárez voted in November of 2012 to ban mining activity on their lands for the next 100 years. The company acknowledged its exploration program in Benito Juárez is currently inactive, claiming it is "working through delays in the exploration permits for its Cinco de Mayo project."

It is unclear what the future holds for Benito Juárez, a town steeped in mine-related conflict in a region where various armed actors—police, the army and organized crime groups—act with impunity.

One thing seems certain: the rural way of life passed on through generations will continue to provide for families, and locals will do everything in their power to protect the lands and waters from irresponsible use and contamination. For Ismael and Manuela’s youngest son Uriel, orphaned at 18, the lands farmed by his father are the key to his future.

“It’s what I like,” he said, as we drove through the sun-baked roads along his family’s land. “Working with animals, agriculture, and everything related to the farm.”

Click here for more details on how the company's representatives interacted with the ejido of Benito Juárez. Click here to read a letter from members of the Barzón to the Canadian Ambassador to Mexico.

Dawn Paley is a freelance journalist and editor member of the Media Co-op. Her work is published online at dawnpaley.ca.